Although the printing press had been invented in 1450 by Johann Gutenburg in Germany (161 years before the 1611 printing), the equipment used by the printer had changed very little. Printing was still very slow and difficult. All type was set by hand, one piece at a time Backwards, by candle or Lamp (that’s one piece at a time through the whole Bible), and errors were an expected part of any completed book. Because of this difficulty and also because the 1611 printers had no earlier editions from which to profit, the very first edition the King James Version had a number of printing errors. As shall later be demonstrated, these were not the sort of textual alterations, which are freely made in modern bibles. They were simple, obvious printing errors of the sort that can still be found at times in recent editions even with all of the advantages of useless, but they should be corrected in later editions.

The two original printings of the Authorized Version demonstrate the difficulty of printing in 1611 without making mistakes. Both editions were printed in Oxford. Both were printed in the same year: 1611. The same printers did both jobs. Most likely, both editions were printed on the same printing press. Yet, in a strict comparison of the two editions, approximately 100 textual differences can be found. In the same vein the King James critics can find only about 400 alleged textual alterations in the King James Version after 375 years of printing and four so-called revisions! Something is rotten in Scholarsville! The time has come to examine these “revisions.”

II THE FOUR SO-CALLED REVISIONS OF 1611 KJV

Much of the information in this section is taken from a book by F.H.A. Scrivener called The Authorized Edition of the English Bible (1611), Its Subsequent Reprints and Modern Representatives. This book is as pedantic as its title indicates. The interesting point is that Scrivener, who published this book in 1884, was a member of the Revision Committee of 1881. He was not a King James Bible believer, and therefore his material is not biased toward the Authorized Version.

In the section of Scrivener’s book dealing with the KJV “revisions,” one initial detail is striking. The first two so-called major revisions of the King James Bible occurred within 27 years of the original printing. (The language must have been changing very rapidly in those days.) The 1629 edition of the Bible printed in Cambridge is said to have been the first revision. A revision it was not, but simply a careful correction of earlier printing errors. Not only was this edition completed just eighteen years after the translation, but two of the men who participated in this printing, Dr. Samuel Ward and John Bois, had worked on the original translation of the King James Version. Who better to correct early errors than two that had worked on the original translation! Only nine years later and in Cambridge again, another edition came out which is supposed to have been the second major revision. Both Ward and Bois were still alive, but it is not known of they participated at this time. But even Scrivener, who as you remember worked on the English Revised Version of 1881, admitted that the Cambridge printers had simply reinstated words and clauses overlooked by the 1611 printers and amended manifest errors. According to a study which will be detailed later, 72% of the approximately 400 textual corrections in the KJV were completed by the time of the 1638 Cambridge edition, only 27 years after the original printing!

Just as the first two so-called revisions were actually two stages of one process: the purification of early printing errors, so the last two so-called revisions were two stages in another process: the standardization of the spelling. These two editions were only seven years apart (1762 and 1769) with the second one completing what the first had started. But when the scholars are numbering revisions, two sounds better than one. Very few textual corrections were necessary at this time. The thousands of alleged changes are spelling changes made to match the established correct forms. These spelling changes will be discussed later. Suffice it to say at this time that the tale of four major revisions is truly a fraud and a myth. But you say there are still changes whether they are few or many. What are you going to do with the changes that are still there? Let us now examine the character of these changes.

III THE SO-CALLED THOUSANDS OF CHANGES

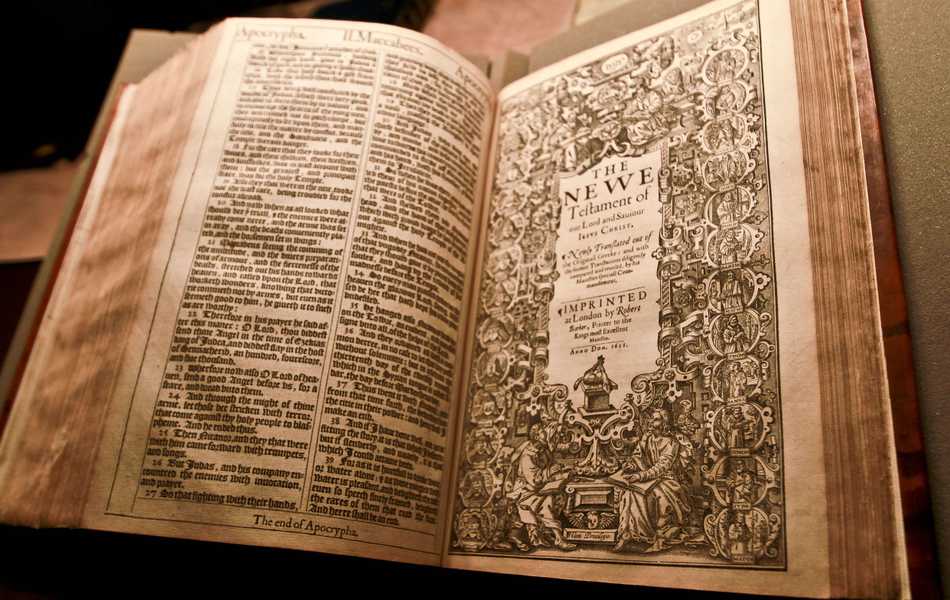

Suppose someone were to take you to a museum to see an original copy of the King James Version. You come to the glass case where the Bible is displayed and look down at the opened Bible through the glass. Although you are not allowed to flip through its pages, you can readily tell that there are some very different things about this Bible from the one you own. You can hardly read its words, and those you can make out are spelled in odd and strange ways. Like others before you, you leave with the impression that the King James Version has undergone a multitude of changes since its original printing in 1611. But beware, you have just been taken by a very clever ploy. The differences you saw are not what they seem to be. Let’s examine the evidence.

PRINTING CHANGES

For proper examination, the changes can be divided into three kinds: printing changes, spelling changes, and textual changes. Printing changes will be considered first. The type style used in 1611 by the KJV translators was the Gothic Type Style. The typestyle you are reading right now and are familiar with is Roman Type. Gothic Type is sometimes called Germanic because it originated in Germany. Remember that that is where printings were invented. The Gothic letters were formed to resemble the hand-drawn manuscript lettering of the Middle ages. At first, it was the only style in use. The Roman Type Style was invented fairly early, but many years passed before it became the predominate style in most European countries. Gothic continued to be used in Germany until recent years. In 1611 in England, Roman Type was already very popular and would soon supersede the Gothic. However, the original printers chose the Gothic Style for the KJV because it was considered to be more beautiful and eloquent than the Roman. But the change to Roman Type was not long in coming. In 1612, the first King James Version using Roman Type was printed. Within a few years, all the Bibles printed used the Roman Type Style.

Please realize that a change in type style no more alters the text of the Bible than a change in format or type size does. However, the modern reader who has not become familiar with Gothic can find it very difficult to understand. Besides some general change in form, several specific letter changes need to be observed. For instance, the Gothic s looks like the Roman s when used as a capital letter or at the end of a word. But when it is used as a lower case s at the beginning or in the middle of a word, the letter looks like our f. Therefore, also becomes alfo and set becomes fet. Another variation is found in the German v and u. The Gothic v looks like a Roman u while the Gothic u looks like the Roman v. This explains why our w is called a double-u and not a double-v. Sound confusing? It is until you get used to it. In the 1611 edition, love is loue, us is vs, and ever is euer. But remember, these are not even spelling changes. They are simply type style changes. In another instance, the Gothic j looks like our i. So Jesus becomes Iefus (notice the middle s changed to f) and Joy becomes ioy. Even the Gothic d is shaped quite differently from the Roman d with the stem leaning back over the circle in a shape resembling that of the Greek Delta. These changes account for a large percentage of the “thousands” of changes in the KJV, yet they do no harm whatsoever to the text. They are nothing more than a smokescreen set up by the attackers of our English Bible.

SPELLING CHANGES

Another kind of change found in the history of the Authorized Version are changes of orthography or spelling. Most histories date the beginning of Modern English around the 1500. Therefore, by 1611 the grammatical structure and basic vocabulary of present-day English had long been established. However, the spelling did not stabilize at the same time. In the 1600’s spelling was according to whim. There was no such thing as correct spelling. No standards had been established. An author often spelled the same word several different ways, often in the same book and sometimes on the same page. And these were the educated people. Some of you reading this today would have found the 1600’s a spelling paradise. Not until the eighteenth century did the spelling begin to take a stable form. Therefore, in the last half of the eighteenth century, spelling of the King James Version of 1611 was standardized.

What kind of spelling variations can you expect to find between your present edition and the 1611 printing? Although every spelling difference cannot be categorized, several characteristics are very common. Additional e’s were often found at the end of the words such as feare, darke, and beare. Also, double vowels were much more common than they are today. You would find mee, bee, and mooued instead me, be, and moved. Double consonants were also much more common. What would ranne, euill, and ftarres be according to present-day spelling? See if you can figure them out. The present-day spellings would be ran, evil, and stars. These typographical and spelling changes account for almost all of the so-called thousands of changes in the King James Bible. None of them alter the text in any way. Therefore they cannot be honestly compared with thousands of true textual changes which are blatantly made in the modern versions.

TEXTUAL CHANGES

Almost all of the alleged changes have been accounted for. We now come to the question of actual textual differences between our present edition and that of 1611. There are some differences between the two, but they are not the changes of a revision. They are instead the correction of early printing errors. That this is a fact may be seen in three things: That this is a fact may be seen in three things: 1) the character of the changes, 2) the frequency of the changes throughout the Bible, and 3) the time the changes were made. First, let us look at the character of the changes were made. First, let us look at the character of the changes made from the time of the first printing of the Authorized English Bible.

The changes from the 1611 edition that are admittedly textual are obviously printing errors because of the nature of these changes. They are not textual changes made to alter the reading. In the first printing, words were sometimes inverted. Sometimes a plural was written as singular or visa versa. At times a word was miswritten for one that was similar. A few times a word or even a phrase was omitted. The omissions were obvious and did not have the doctrinal implications of those found in modern translations. In fact, there is really no comparison between the corrections made in the King James text and those proposed by the scholars of today.

F. H. A. Scrivener, in the appendix of his book, lists the variations between the 1611 edition of the KJV and later printings. A sampling of these corrections is given below. In order to be objective, the samples give the first textual correction on consecutive left-hand pages of Scrivener’s book. The 1611 reading is given first; then the present reading: and finally, the date the correction was first made.

- this thing – this thing also (1638)

- shalt have remained – ye shall have remained (1762)

- Achzib, nor Helbath, nor Aphik – of Achzib, nor of Helbath, nor of Aphik (1762)

- requite good – requite me good (1629)

- this book of the Covenant – the book of this covenant (1629)

- chief rulers – chief ruler (1629)

- And Parbar – At Parbar (1638)

- For this cause – And for this cause (1638)

- For the king had appointed – for so the king had appointed (1629)

- Seek good – seek God (1617)

- The cormorant – But the cormorant (1629)

- returned – turned (1769)

- a fiery furnace – a burning fiery furnace (1638)

- The crowned – Thy crowned (1629)

- thy right doeth – thy right hand doeth (1613)

- the wayes side – the way side (1743)

- which was a Jew – which was a Jewess (1629)

- the city – the city of the Damascenes (1629)

- now and ever – both now and ever (1638)

- which was of our father’s – which was our fathers (1616)

Before your eyes are 5% of the textual changes made in the King James Version in 375 years. Even if they were not corrections of previous errors, they would be of no comparison to modern alterations. But they are corrections of printing errors, and therefore no comparison is at all possible. Look at the list for yourself and you will find only one that has serious implications. In fact, in an examination of Scrivener’s entire appendix, it is the only variation found by this author that could be accused of being doctrinal. I am referring to Psalm 69:32 where the 1611 edition has “seek God.” Yet, even with this error, two points demonstrate that this was indeed a printing error. First, the similarity of the words “good” and “God” in spelling shows how easily a weary typesetter could misread the proof and put the wrong word in the text. Second, this error was so obvious that it was caught and corrected in the year 1617, only six years after the original printing and well before the first so-called revision. The myth that there are several major revisions to the 1611 KJV should be getting clearer.Only approximately 400 variations are named between the 1611 edition and modern copies. Remember that there were 100 variations between the first two Oxford editions which were both printed in 1611.

The character and frequency of the textual changes clearly separate them from modern alterations. But the time the changes were made settles the issue absolutely. The great majority of the 400 corrections were made within a few years of the original printing. Take, for example, our earlier sampling. Of the twenty corrections listed, one was made in 1613, one in 1616, one in 1617, eight in 1629, five in 1638, one in 1743, two in 1762, and one in 1769. That means that 16 out of 20 corrections, or 80%, were made within twenty-seven years of the 1611 printing. That is hardly the long drawn out series of revisions the scholars would have you to believe. In another study made by examining every other page of Scrivener’s appendix in detail, 72% of the textual corrections were made by 1638. There is no “revision” issue.

The character of the textual changes is that of obvious errors. The frequency of the textual changes is sparse, occurring only once per three chapters. The chronology of the textual changes is early with about three fourths of them occurring within twenty-seven years of the first printing. All of these details establish the fact that there were no true revisions in the sense of updating the language or correcting translation errors. There were only editions which corrected early typographical errors. Our source of authority for the exact wording of the 1611 Authorized Version is not in the existing copies of the first printing. Our source of authority for the exact wording of our English Bible is in the preserving power of Almighty God. Just as God did not leave us the original autographs to fight and squabble over, so He did not see fit to leave us the proof copy of the translation. Our authority is in the hand of God as always. You can praise the Lord for that!