Faithful found,

Faithful among the faithless, Faithful only he …

Among innumerable false ~

Unmoved, unshaken, unseduced, unterrified;

His loyalty he kept, his love, his zeal …

Nor number, nor example with him wrought

To swerve from Truth

Or change his constant mind

Tho’ single.

John Wycliff’s hand-written manuscripts were the first complete Bibles in the English language (1380’s). Wycliff (or Wycliffe), an Oxford theologian translated out of the fourth century Latin Vulgate, as the Greek and Hebrew languages of the Old and New Testaments were inaccessible to him. Curiously, he was also the inventor of bifocal eyeglasses. Wycliff spent many of his years writing and teaching against the practices and dogmas of the Roman Church which he believed to be contrary to the Holy Writ. Though he died a nonviolent death, the Pope was so infuriated by his teachings that 44 years after Wycliff had died, he ordered the bones to be dug-up, crushed, and scattered in the river!

Gutenburg invented the printing press in the 1450’s, and the first book to ever be printed was the Bible (in Latin). With the onset of the Reformation in the early 1500’s, the first printings of the Bible in the English language were produced illegally and at great personal risk of those involved.

William Tyndale was the Captain of the Army of English reformers, and in many ways their spiritual leader. His work of translating the Greek New Testament into the plain English of the ploughman was made possible through Erasmus’ publication of his Greek/Latin New Testament printed in 1516. Erasmus and the printer and reformer John Froben published the first non-Latin Vulgate text of the Bible in a millennium.

For centuries Latin was the language of scholarship and it was widely used amongst the literate. Erasmus’ Latin was not the Vulgate translation of Jerome, but his own fresh rendering of the Greek New Testament text that he had collated from six or seven partial New Testament manuscripts into a complete Greek New Testament.

Erasmus’ translation from the Greek revealed enormous discrepancies in the Vulgate’s integrity amongst the rank and file scholars, many of whom were already convinced that the established church was doomed by virtue of its evil hierarchy. Pope Leo X’s declaration that “the fable of Christ was very profitable to him” infuriated the people of God.

With Erasmus’ 1516 translation, the die was cast. In 1517 Martin Luther nailed his 95 Theses of Contention to the Wittenberg Door. Luther, who would be exiled in the months following the Diet of Worms Council in 1521 that was designed to martyr him, would translate the New Testament into German from Erasmus’ Greek/Latin New Testament and publish it in September of 1522. William Tyndale would do the same into English. It could not, however, be done in England.

Laboring under Luther’s shadow, in the relative safety of Cologne and Worms, Tyndale worked to completed his New Testament in English. Tyndale was fluent in eight languages and is considered by many to be the primary architect of the modern English language. Already hunted because of the rumor spread abroad that such a project was underway, inquisitors and bounty hunters were on Tyndale’s trail to abort the effort. God foiled their plans, and in 1525/6 Tyndale printed the first English New Testament. The Bishop of London sought to confiscate and burn them, but copies continued to be smuggled into England. The more the King and Bishop resisted its distribution, the more fascinated the public at large became. Bishop Tunstal declared that Tyndale’s translation contained thousands of errors as they torched hundreds of New Testaments confiscated by the clergy. One risked death by burning if caught in mere possession of the forbidden books.

Like the Pharisees of old, the clergy realized that having God’s Word available to the people in the language of common English, would mean disaster to the church. No longer could they control access to the scriptures. If people were able to read the Bible in their own tongue, the church’s income and power would crumble. They could not continue the selling of indulgences (the forgiveness of sins) or bartering the release of loved ones from “Purgatory”. People would begin to challenge the church’s authority if the practices of the church were exposed to the light of Scripture. The contradictions between God’s Word and what the priests taught, would open the “eyes of the blind” and the truth would set them free. Salvation by GRACE alone — through faith (not by works) would be revealed. The need for “priest craft” would give way to the priesthood of all believers. The veneration of canonized Saints and of the Virgin would be called into question. The availability of the scriptures in English was the greatest threat imaginable to the corrupted Romish church. The Church of Rome would never give up without a fight.

Tyndale’s New Testament was the first ever printed in the English language. Its first printing occurred in 1525/6, but only two complete copies of that first printing are known to have survived. Any Edition printed before 1570 is very rare and valuable, particularly pre-1540 editions and fragments. Tyndale’s flight was an inspiration to freedom loving Englishmen who drew courage from the 11 years that he was hunted. Books and Bibles flowed into England in bales of cotton and sacks of wheat. In the end, Tyndale was caught: betrayed by an Englishman that he had befriended. Tyndale was incarcerated for 500 days before he was strangled and burned at the stake in 1536. His last words were, “Lord, open the eyes of the King of England”.

Myles Coverdale and John Rogers were loyal assistants the last six years of Tyndale’s life, and they carried the project forward. Coverdale finished translating the Old Testament, and in 1535 he printed the first complete Bible in the English language, making use of Luther’s German text and the Latin as sources. Thus, the first complete English Bible was printed on October 4, 1535, and is known as the Coverdale Bible.

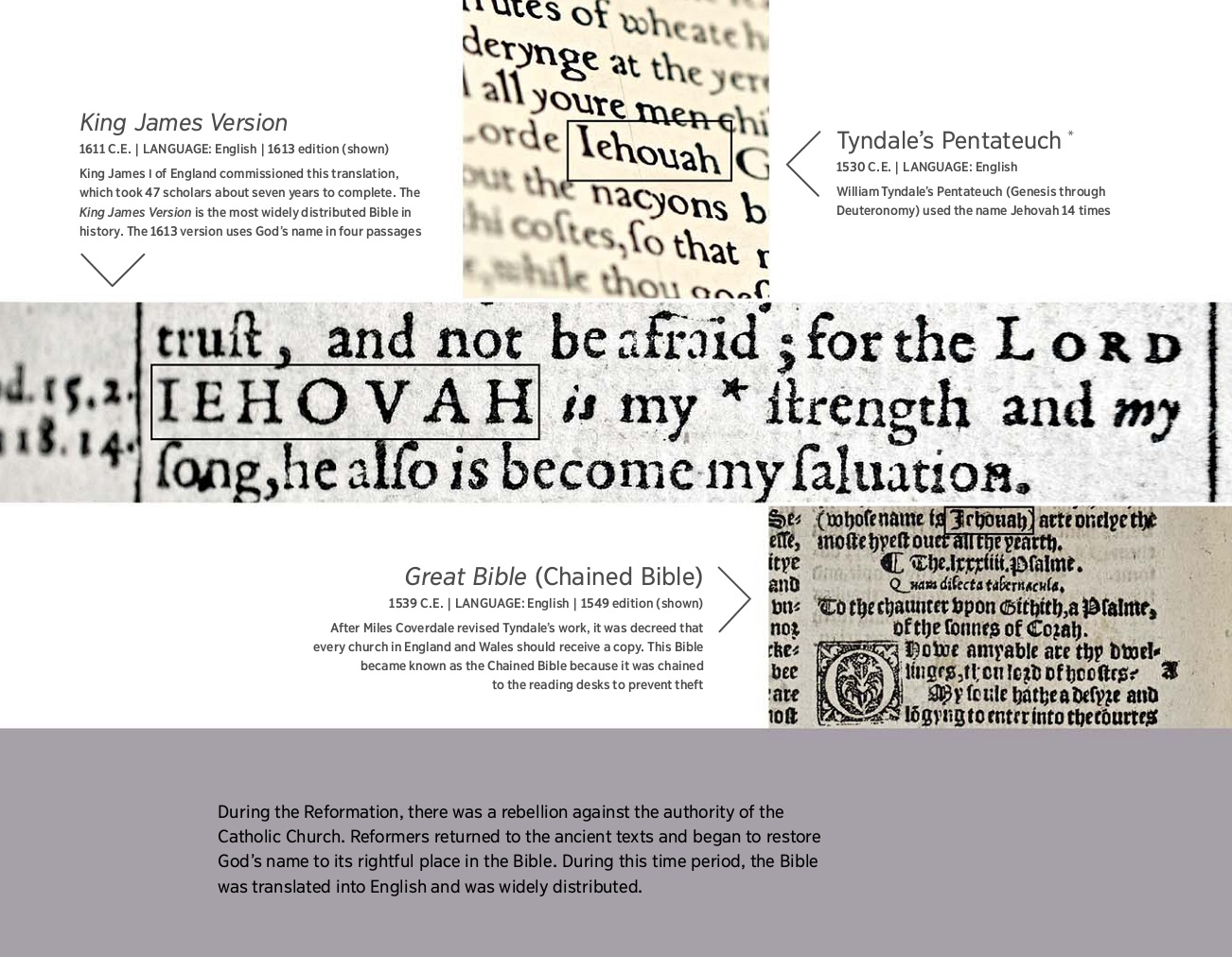

John Rogers went on to print the second complete English Bible in 1537. He printed it under the pseudonym “Thomas Matthew“, as a considerable part of this Bible was the translation of Tyndale, whose writings had been condemned by the English authorities. It is a composite made up of Tyndale’s Pentateuch and New Testament (1534-1535 edition) and Coverdale’s Bible and a small amount of Roger’s own translation of the text. It remains known most commonly as the Matthew’s Bible.

In 1539, Thomas Cranmer, the Archbishop of Canterbury, hired Myles Coverdale at the bequest of King Henry VIII to publish the “Great Bible“. It became the first English Bible authorized for public use, as it was distributed to every church, chained to the pulpit. By the decree of the king a reader was provided so that the illiterate could hear the Word of God in their own tongue. It would seem that William Tyndale’s last prayer had been granted — three years after his martyrdom.

Cranmer’s Bible, published by Coverdale, was known as the Great Bible due to its great size: a large pulpit folio measuring over 14 inches tall. Seven editions of this version were printed between April of 1539 and December of 1541.

The ebb and flow of freedom continued through the 1540’s and into the 1550’s. The reign of Queen Mary (“Bloody Mary“) was the next obstacle to the printing of the Bible in English. She was possessed in her quest to return England to the Romish Church. In 1555, John Rogers (“Thomas Matthew”) and Thomas Cranmer were both burned at the stake. Mary went on to burn reformers at the stake by the hundreds for the “crime” of being a Protestant. This era was known as the Marian Exile, and the refugees fled from England with little hope of ever seeing their home or friends again.

In the 1550’s, the Church at Geneva, Switzerland, was very sympathetic to the reformer refugees and was one of only a few safe havens for a desperate people. Many of them met in Geneva, led by Myles Coverdale and John Foxe (publisher of the famous Foxe’s Book of Martyrs, which is to this day the only exhaustive reference work on the persecution and martyrdom of Early Christians and Protestants from the first century up to the mid-16th century), as well as Thomas Sampson and William Whittingham. There, with the protection of John Calvin and John Knox, the Church of Geneva determined to produce a Bible that would educate their families while they continued in exile.

The New Testament was completed in 1557, and the complete Bible was first published in 1560. It became known as the Geneva Bible. Due to a passage in Genesis describing the clothing that God fashioned for Adam and Eve upon expulsion from the Garden of Eden as “Breeches” (an antiquated form of “Britches”), some people referred to the Geneva Bible as the Breeches Bible.

The Geneva Bible was the first Bible to add verse numberings to the chapters, so that referencing specific passages would be easier. Every chapter was also accompanied by extensive marginal notes and references so thorough and complete that the Geneva Bible is also considered the first English “Study Bible”. The works of Shakespeare contain many quotes from the Geneva translation. The Geneva Bible became the Bible of choice for over 100 years of English speaking Christians. Between 1560 and 1644 at least 144 editions of this Bible were published. Examination of the 1611 King James Bible demonstrates the great influence of the Geneva Bible, and thus the influence of Tyndale. The Geneva Bible retains approximately 90% of William Tyndale’s translation. For many decades, the Geneva Bible remained more popular than that authorized by King James. It holds the honor of being the first Bible taken to America, and the Bible of the Puritans and Pilgrims.

With the end of Queen Mary’s bloody reign, the reformers could safely return to England. The Anglican Church, under Queen Elizabeth I, reluctantly tolerated the printing and distribution of the Geneva Bible in England. The marginal notes, which were vehemently against the institutional Church of the day, did not rest well with many in authority. Another version, one with a less inflammatory tone was desired. In 1568, the Bishop’s Bible was introduced. Despite 19 printing between 1568 and 1606, the version never gained popularity among the people. The Geneva version was simply too trusted to compete with.

By the 1580’s, the Roman Church understanding that God’s Word could not be held captive, surrendered it’s fight for “Latin only”. Using the Latin Vulgate as a source text, they went on to publish an English Bible with all the distortions and corruptions that Erasmus had decried 75 years earlier. Because it was translated at the Catholic College in the city of Rheims, it was known as the Rheims (or Rhemes) New Testament. The Old Testament was translated by the Church of Rome in 1609 at the College in the city of Doway (also spelled Douay and Douai). The combined product is commonly referred to as the “Doway/Rheims” Version.

In 1589, Dr. Fulke of Cambridge published the “Fulke’s Refutation“, in which he printed in parallel columns the Bishops Version along side the Rheims Version, attempting to show the distortion of the Roman Church’s corrupt compromise of an English version of the Bible.

With the death of Queen Elizabeth I, Prince James VI of Scotland became King James I of England. The Protestant clergy approached the new King in 1604 and announced their desire for a new translation to replace the Bishop’s Bible first printed in 1568. They knew that the Geneva Version had won the hearts of the people because of its excellent scholarship, accuracy, and exhaustive commentary. However, they did not want the controversial marginal notes (proclaiming the Pope an Anti-Christ, etc.) Essentially, the leaders of the church desired a Bible for the people, with scriptural references only for word clarification when multiple meanings were possible.

This “translation to end all translations” (for a while at least) was the result of the combined effort of about fifty scholars. They relied heavily on Tyndale’s New Testament, The Coverdale Bible, The Matthews Bible, The Great Bible, The Geneva Bible, and even used the Rheims New Testament. The great revision of the Bishop’s Bible had begun. From 1605 to 1606 the scholars engaged in private research. From 1607 to 1609 the work was assembled. In 1610 the work went to press, and in 1611 the first of the huge (16 inch tall) pulpit folios known as “The King James Bible” came off the printing press.

A typographical error in Ruth 3:15 rendered the pronoun “He” instead of the correct “She” in that verse. This caused some of the 1611 First Editions to be known by collectors as “He” Bibles, and others as “She” Bibles.

It took many years for it to overtake the Geneva Bible in popularity with the people, but eventually the King James Version became the Bible of the English people. It became the most printed book in the history of the world. In fact, for around 250 years, until the appearance of the Revised Version of 1881, the King James Version reigned without a rival.

Although the first Bible printed in America was done in the native Algonquin Indian Language (by John Eliot in 1663), the first English language Bible to be printed in America (byRobert Aitken in 1782) was a King James Version. In 1791, Isaac Collins vastly improved upon the quality and size of the typesetting of American Bibles and produced the first “Family Bible” printed in America — also a King James Version. That same year Isaiah Thomas published the first Illustrated Bible printed in America — also the King James Version.

In 1841, the English Hexapla New Testament was printed. This wonderful textual comparison tool shows in parallel columns: The 1380 Wycliff, 1534 Tyndale, 1539 Great, 1557 Geneva, 1582 Rheims, and 1611 King James versions of the entire New Testament — with the original Greek at the top of the page.

Consider the following textual comparison of John 3:16 as they appear in many of these famous printings of the English Bible:

1st Ed. King James (1611):

“For God so loued the world, that he gaue his only begotten Sonne: that whosoeuer beleeueth in him, should not perish, but haue euerlasting life.”

Rheims (1582):

“For so God loued the vvorld, that he gaue his only-begotten sonne: that euery one that beleeueth in him, perish not, but may haue life euerlasting”

Geneva (1557):

“For God so loueth the world, that he hath geuen his only begotten Sonne: that none that beleue in him, should peryshe, but haue euerlasting lyfe.”

Great Bible (1539):

“For God so loued the worlde, that he gaue his only begotten sonne, that whosoeuer beleueth in him, shulde not perisshe, but haue euerlasting lyfe.”

Tyndale (1534):

“For God so loveth the worlde, that he hath geven his only sonne, that none that beleve in him, shuld perisshe: but shuld have everlastinge lyfe.”

Wycliff (1380):

“for god loued so the world; that he gaf his oon bigetun sone, that eche man that bileueth in him perisch not: but haue euerlastynge liif,”

It is possible to go back to manuscripts earlier than Wycliff, but the language is not easily recognizable.

For example, the Anglo-Saxon manuscript of 995 ADrenders John 3:16 as:

God lufode middan-eard swa, dat he seade his an-cennedan sunu, dat nan ne forweorde de on hine gely ac habbe dat ece lif.